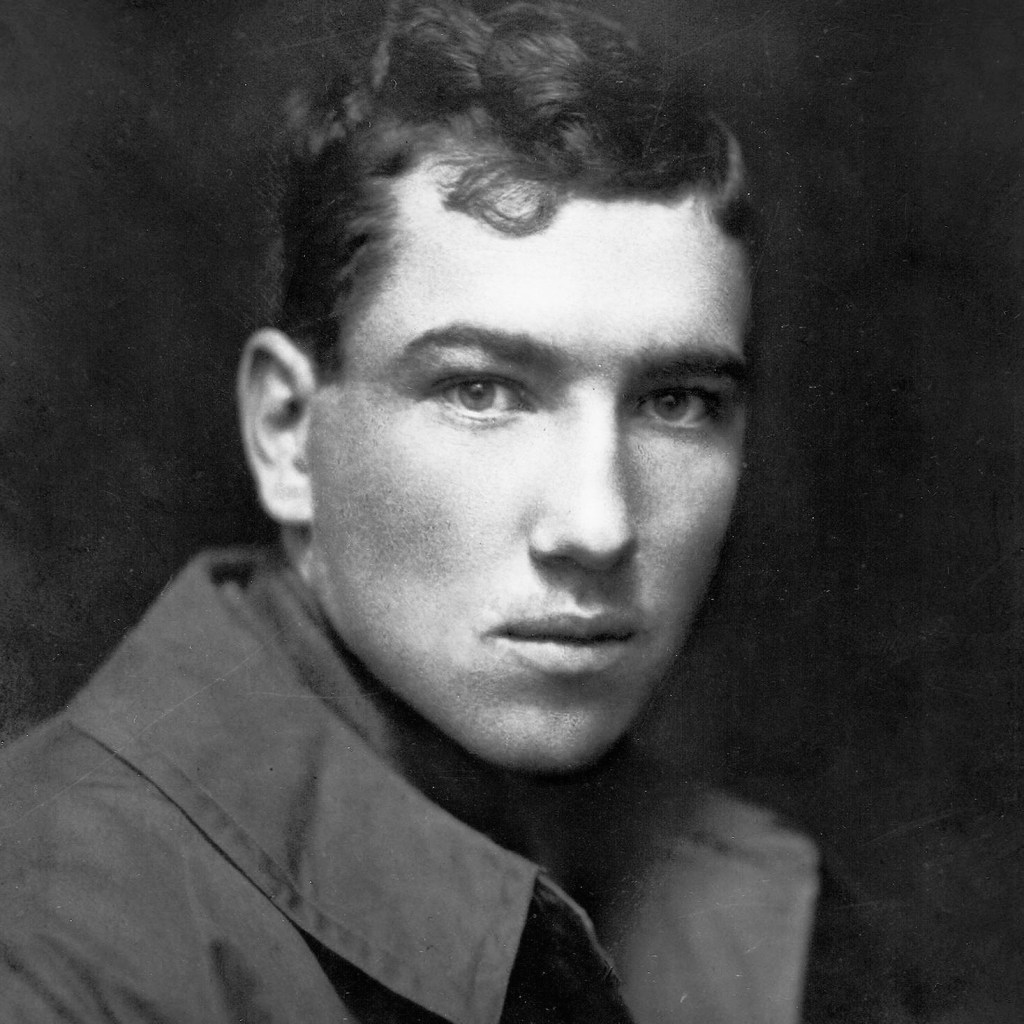

English writer, soldier and historian Robert Graves was BOTD in 1895. Born in London to a prominent Irish family, his father Alfred Graves was a leading poet in the Gaelic literary revival of the late 19th century. A bright but sickly child, he won a scholarship to Charterhouse, a prestigious independent boys’ school, where he began writing poetry and had a passionate affair with a younger classmate. Awarded a scholarship to Oxford University, he delayed his studies and joined the British Army in World War One. After sustaining serious injuries at the Somme, he was invalided back to England, publishing his first poetry collection, Over the Brazier, in 1916. Like his friend and fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon, Graves’ depiction of trench warfare was graphic, disturbing and anti-patriotic, attracting praise and considerable controversy. In 1917, he helped Sassoon avoid a military court-martial by having him sent to Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland, where they were both treated for shell-shock. Their intense, erotically-charged correspondence suggests a sexual relationship, denied by both men in later life. Returning to battle, Graves deserted his post after contracting influenza, returning to England where he persuaded a demobilisation officer to discharge him from the Army. After the war, he married Nancy Nicholson in 1918 and moved to Oxford to complete his degree, where he befriended T. E. Lawrence. After graduating, he moved to Cairo in 1926 to take up a teaching post, accompanied by Nicholson, their four children and his mistress Laura Riding. He and Nicholson separated soon after, and Graves and Riding moved to Mallorca in Spain, where they founded a printing press and edited the literary journal Epilogue. They had an open relationship, with Riding alternating between Graves and her lover Geoffrey Phibbs. Graves achieved major commercial success in 1927 with Lawrence and the Arabs, a romanticised biography of Lawrence that helped establish his subject’s status as a folk hero. After Riding attempted suicide in 1929, Graves published a memoir Good-Bye to All That, reputedly as a way of paying Riding’s medical bills. It became a critical and commercial success, notable for his frank descriptions of his schoolboy homosexual experiences, harrowing battle experiences and complex relationship with Sassoon. Enraged by Graves’ depiction of him as suicidal and a closeted homosexual, Sassoon ended their friendship, spending the rest of his life attempting to discredit Graves’ work. Undeterred, Graves achieved further success in 1934 with I, Claudius, an historical biography of the titular pRoman emperor. A sequel, Claudius the Good, followed in 1935, winning Graves the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Graves and Riding moved to the United States, eventually separating in 1940. He returned to England alone, where he formed a relationship with Beryl Hodge, marrying in 1950 and having four children. He continued writing, achieving huge success with 1955’s The Greek Myths, his prose retelling of Greek myths and legends, which became standard reading for generations of British schoolchildren. His career was severely damaged in 1967 when he collaborated with Oma Ali-Shah on a new translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, using a source text that was later revealed as a forgery. He retired from writing in the early 1970s, but enjoyed a major resurgence in popularity with the successful 1976 TV adaptation of I, Claudius, starring Derek Jacobi as the stuttering emperor and John Hurt as a flagrantly queer Caligula. After suffering from dementia for many years, he died in 1985 aged 90.

Robert Graves