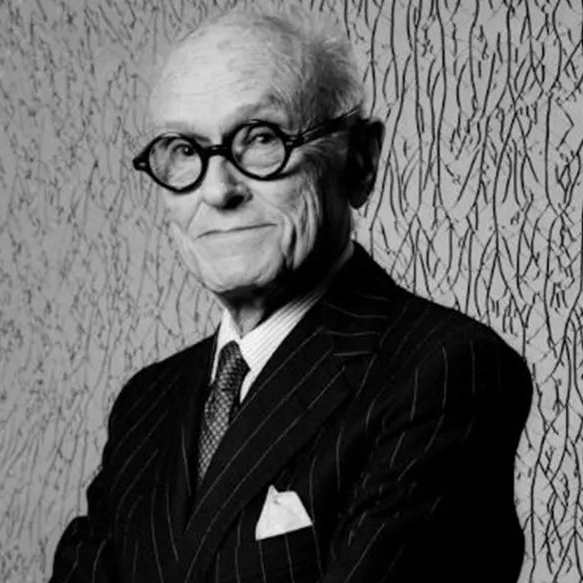

American architect Philip Johnson was BOTD in 1906. Born in Cleveland, Ohio to a wealthy upper-middle-class family, he was educated at private schools and studied philosophy at Harvard University. After graduating, he visited Germany, meeting modernist architects Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and Miles van der Rohe. He also witnessed the rise of the Nazi Party and attended an Nuremberg Rally, becoming enraptured by blond boys in black leather. He returned to New York in 1932, financing and becoming the first director of the architecture department at the Museum of Modern Art. His 1932 manifesto The International Style: Architecture Since 1932, co-written with Henry-Russell Hitchcock, set out his theories of architectural modernism, largely ignoring the movement’s egalitarian vision. In 1934, he resigned from MoMa and pursued a career as a journalist and political aide. He became a prominent supporter of the Nazi Party, writing a positive review of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and financed the creation of fascist para-military organisations in the United States. In 1939, he travelled to Europe on a press tour to report on the impending war, describing the Nazi invasion of Poland as “a stirring spectacle”. He returned to Harvard in 1940 to study architecture, hastily renouncing his pro-Nazi views after the United States entered World War Two. Drafted into the US Army, he was later investigated by the FBI for potential collaboration with the German government. After the war, he returned to his role at MoMA, and designed a minimalist glass rectangle for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut. Known as “The Glass House”, it earned him significant public attention. In 1956, he and van der Rohe worked on the Seagram Building in New York City, which became a landmark of modernist architecture. His other notable designs include a modernist sculpture garden at MoMA, the David Kock Theatre at Lincoln Centre in New York, the Dumbarton Oaks art gallery in Washington, D.C., and the IDS Center in Minneapolis. In 1960, he began a relationship with David Whitney, who became his life partner, socialising with a gay artistic circle that included Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, John Cage and Andy Warhol. By the 1980s, he was one of the most prestigious and highly-paid corporate architects in the world. “I’m a whore,” he once said in an interview, “and I am paid very well for building high-rise buildings.” His 1984 design for the AT&T Building on Madison Avenue in New York City, featuring a top resembling a Chippendale cabinet, was hailed as a landmark of postmodernist architecture. In later life, he was awarded the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal and the first Pritzker Architecture Prize. He also mentored a series of younger “star-chitects” including Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid, who, like him, restricted their commissions to high-concept corporate designs and showed little interest in public housing projects. He finally acknowledged his homosexuality in 1993, dying in 2005, aged 98. His reputation remains controversial, particularly in light of his wartime political beliefs and for kow-towing to corporate interests to help fund his work.

Philip Johnson