German historian and writer Golo Mann was BOTD in 1909. Born in Munich and christened Angelus Gottfried Thomas, he was the third child of the writer Thomas Mann, and developed close relationships with his five siblings, notably his elder brother Klaus and sister Erika. A nervous and effeminate child, he was a source of embarrassment to his father, who later wrote in his journals about his sexual attraction to Golo and his other sons. After being educated at the Wilhelms-Gymnasium, he was sent to the Schule Schloss Salem, a Spartan boarding school near Lake Constance. Unusually for a young sissy, he thrived under the school’s harsh discipline and developed a love of hiking. After briefly studying law in Munich, he moved to Berlin to study history and philosophy and enjoy the city’s thriving gay nightlife. During a gap year in Paris, he volunteered as a coal miner to understand “real work”, quitting after developing sore knees and returning to Germany continue his studies. Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 made Thomas an enemy of the state, and he and Katia fled to Switzerland. Golo remained in Munich, helping his three younger siblings (and his parents’ substantial savings) leave the country. After briefly joining his parents in Zurich, he moved to Paris to take up a teaching position, writing for Klaus’ left-wing journal Die Sammlung. In 1936, the Mann family’s German citizenship was revoked. Golo obtained Czech citizenship and moved to Prague, but his studies were again interrupted by the 1939 Nazi invasion of the Sudetenland. He volunteered as a soldier in the Czech Army, and was arrested and sent to a French concentration camp. Released by the intervention of an American aid committee, he travelled across the Pyranees and into Spain, boarding a ship to New York City. In 1940, he, Klaus and Erika lived briefly at February House in Brooklun, a queer artists’ commune with housemates Gypsy Rose Lee, Carson McCullers, W. H. Auden, Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, Paul and Jane Bowles, Lincoln Kirstein and Leonard Bernstein. After teaching briefly at Olivet College in Michigan, he joined the US Army in 1942, working for the Office of Strategic Services in Washington D.C. In 1944, he was sent to London to make German-language radio broadcasts for the Allied Forces, and worked for a military propaganda station in Luxembourg. After the war, he left the Army, staying in Europe to attend the Nuremberg Trials. He relocated to Los Angeles in 1947 where he became a history professor at Claremont Men’s College. His 1958 book German History of the 19th and 20th Century became an immediate bestseller, finally removing him from the shadow of his father. He took issue with Hannah Arendt and other historians whom he saw as “apologists” for the war, arguing that the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust was neither inevitable nor unpreventable. Though a robust defender of the West German Republic, he avoided extremes of left- and right-wing political thought, rejecting any “ism” claiming to have a monopoly on truth. In 1960 he returned to Europe, living at his parents’ house in Zurich and working as a freelance historian and writer. His 1971 biography of the military leader Albrecht von Wallenstein, a decade in the writing, became another unlikely bestseller. Mann lived for many years with Hans Beck, a much younger man whom he legally adopted and supported financially until Beck’s death in 1986. His memoir Erinnerungen und Gedanken: Eine Jugend in Deutschland (Reminiscences and Reflections: A Youth in Germany) painted an unflattering portrait of the Mann family home, with Thomas as an emotionally distant, critical and tyrannical parent. Golo retired to Berzona in Switzerland, living to see the fall of Communism and the reunification of East and West Germany. After suffering a heart attack, he was nursed during his final years by Beck’s widow Ingrid. He died in 1994 aged 85, requesting not to be buried in his family’s plot. A few days before his death, he gave a TV interview, acknowledging his homosexuality and stating “I did not fall in love often. I often kept it to myself, maybe that was a mistake. It also was forbidden, even in America, and one had to be a little careful.”

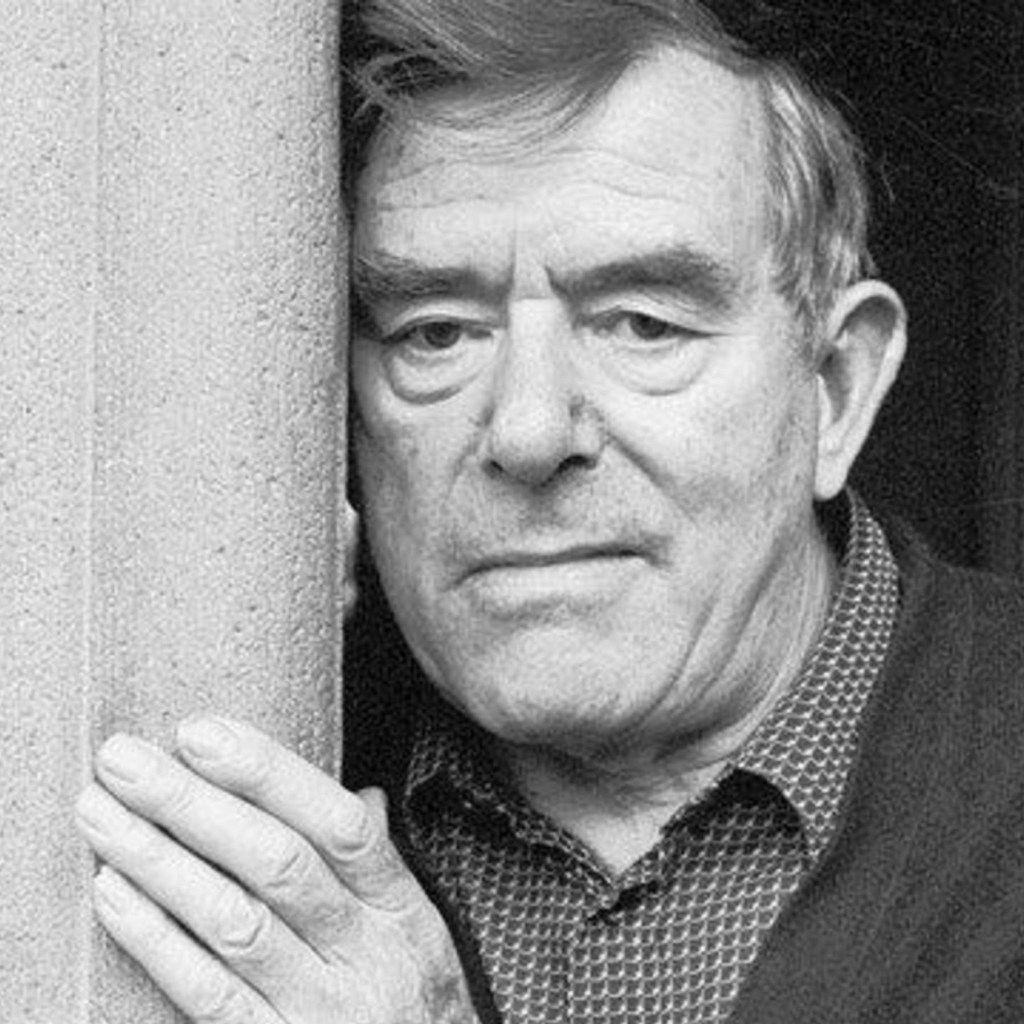

Golo Mann